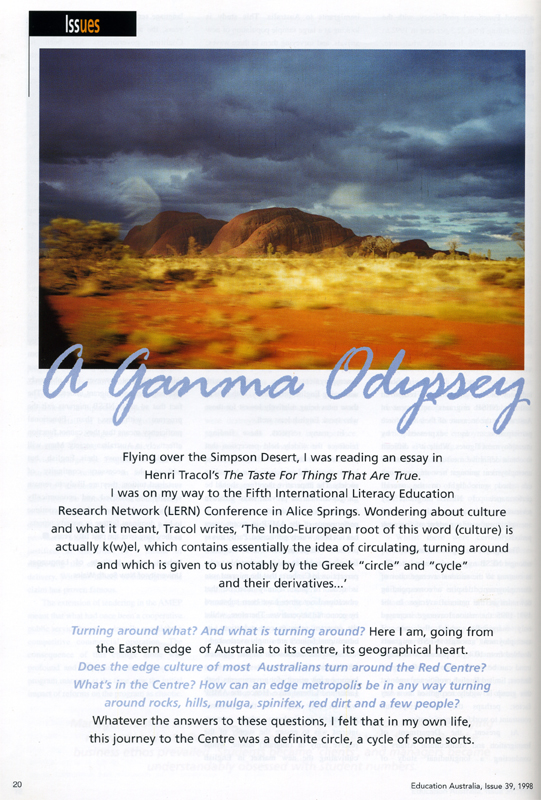

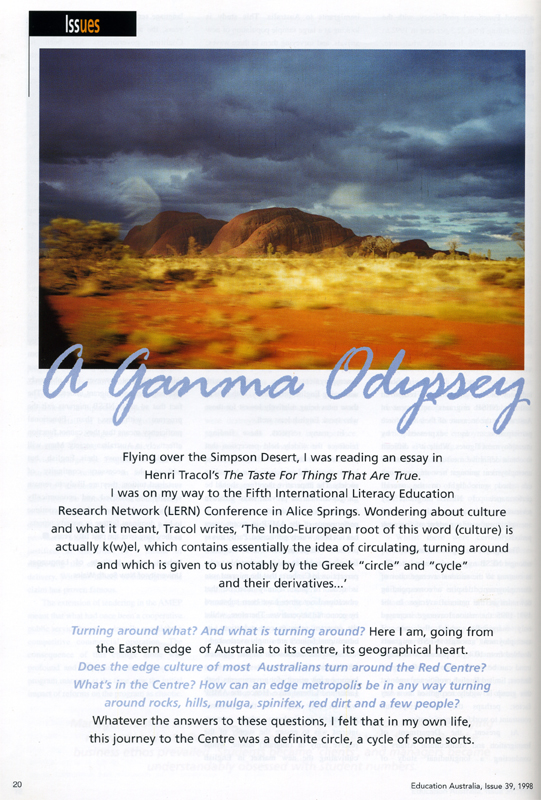

A Ganma OdysseyThe Literacy Education Research Network (LERN) Conference, to most participants, represented far more than a collection of academic papers and workshops and, for Stavros at least, it spanned far longer than just 4 days…

A Ganma OdysseyThe Literacy Education Research Network (LERN) Conference, to most participants, represented far more than a collection of academic papers and workshops and, for Stavros at least, it spanned far longer than just 4 days…

Whatever the answers to these questions, I felt that in my own life, this journey to the Centre was a definite circle, a cycle of some sorts.

It’s been 25 years since I last visited Central Australia. Back then, the Sturt Highway was a two way dirt road all the way from Darwin to near Port Augusta. In 1972, words like revolution, liberation, justice, equality, freedom and peace, rolled off my tongue with a tender passion. Feeling the emptiness in the institutions, the knowledge factories and the general lack of soul in the world I hit the road. Back then I was searching for something. Nowadays, I’m still searching and it seems that the ” R ” word is the only one that doesn’t roll off my tongue so easily. Perhaps it should.

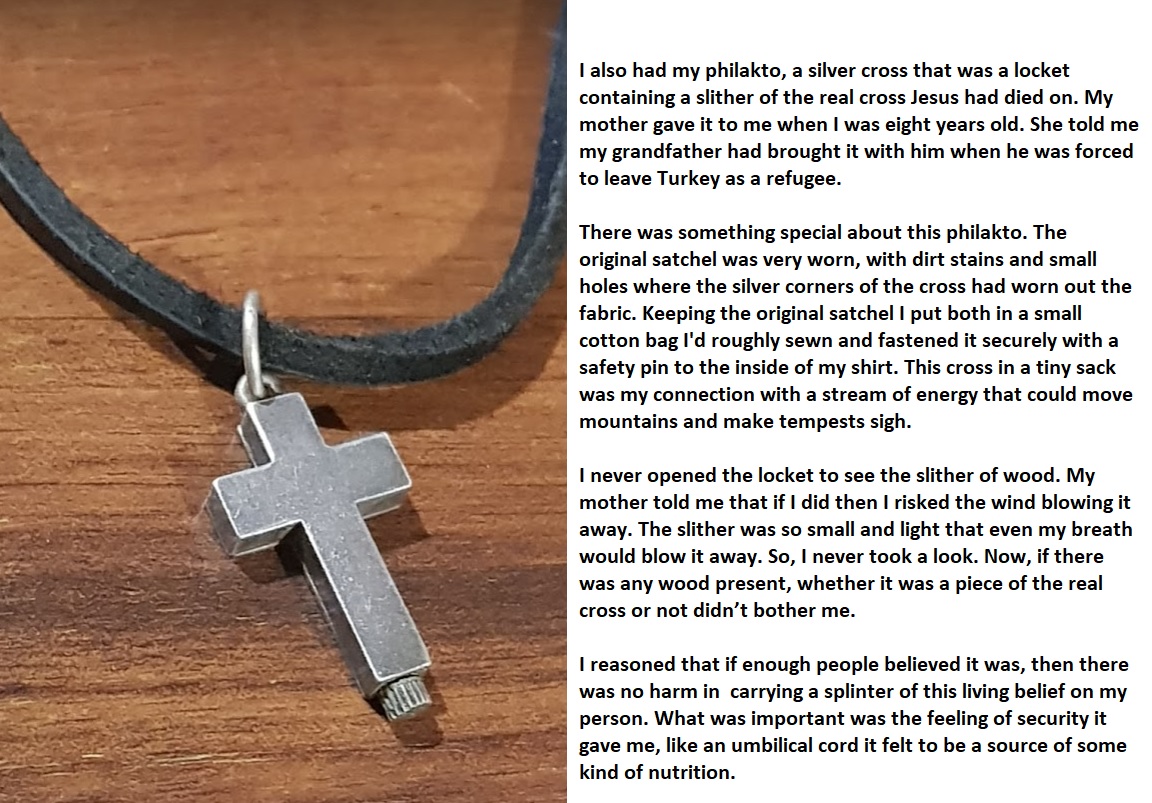

Twenty five years ago I found myself, with little more than nothing, in the heart of Australia. All I had was my canvas pack with a few clothes, a couple of books and some water in a bottle. I had no money. The previous three nights I had slept under the stars along the highway and during the day I prayed for a lift. I was two hours south of Alice heading for Adelaide when I was dropped off at Erldunda, near the turn off to Uluru (Ayers Rock) and Kata Tjuta (The Olgas). Across the road a petrol bowser stood as if on guard outside the general shop. A bus arrived and parked a few metres away from where I was standing. I watched the tourists get off. I hadn’t eaten a thing for over three days and I knew that the people getting off the bus would have something to eat. I approached a woman in a white hat as she stepped off the bus. Looking her in the eyes I said, “Excuse me, have you any food?”.

She looked at me with some pity and reached her hand into a brown paper bag pulling out a small green tomato. As she handed me the fruit I sensed everyone looking at me, from the bus driver to the little girl with her face pressed against the bus window. The white hat woman released the tomato into my hand and a ripple of disgust crossed her eyes and brow. I was dirty, I was homeless, a Dharma Bum now just a bum. I accepted the food and turned away from my shame. I noticed someone standing ahead of me in the distance waving, beckoning me to come over.

I had nothing to lose but everything to gain, holding the unripe tomato in my hand, I walked towards the stranger. As I got closer I could see white hair and a white beard on the face of an old black man. He wore trousers that were a little too big for him and a coat that was a little too small. He smiled and placed his hand on his belly whispering, what sounded like, “Hunger…hunger..” He took me by the arm and showed me to his home by the highway. It was a lean to humpy with a corrugated iron mulga branch roof. Some old flour bags were scattered on the dirt floor to sit on. He shared with me some milk arrowroot biscuit pieces and a powdered milk drink in a tin cup. He let me stay the night. The shop with the petrol bowser had switched its lights off. During the night, nothing much was said between us – the silences, with the occasional bark of a lone dog, said it all.

In the centre of Australia I saw that the dispossessed ones were the generous ones. We non – indigenous ones take and take while these people, the original ones give and give. Twenty five years later, in 1997, our government wants to stop the original people from reestablishing their culture and reconnecting with their land. Extinguishing the recently acquired native title rights is the equivalent of stealing what little these people have and giving this little to the rich, whether pastoralists, miners or just greedy transnational corporations. Will we the non – indigenous ones ever learn? So, 25 years later I was returning with a hunger so subtle that you’d miss it if you weren’t seeking it. It’s a hunger for something which may transform the hole in my being to the whole.

The LERN Conference promised an exploration into multiliteracies, cross cultural communication, anti- racism education and multicultural multimedia all under the theme of Learning. I didn’t know if my hunger would be satisfied attending the Conference. I was hoping for a taste, even a sniff of something that’s true. I closed the book and through the plane’s window noticed below us a road leading out of the desert. In the distance, over the desert and the dunes we could see it came from Alice Springs.

The next morning I arrived at the Araluen Arts Centre in Alice Springs for the Opening Ceremony of the Conference. After the introduction and welcome by the traditional elders from Alice Springs, the Larumba Traditional Women’s Dance Group danced and sang traditional stories that could have a heritage far older than 100,000 years. The singing reminded me of Byzantine chants in the Greek Orthodox Church. The more I listened the more resonances I could hear, like echoes, reminding me of other sacred utterances I had heard – a Sufi zikhr to a Buddhist chant, a Hindu mantra and a native American prayer. It was almost as if there exists just one sacred song with many different versions vibrating through humanity’s common voice. It was fitting that the singing touched these notes because we were an international gathering.

I tried to make sense of the dance movements and resorted to number and rhythm. I was hoping that by keeping count of the position changes and the number of people moving in my awareness, would like insect repellent, keep away unnecessary inner talk. What was before me could not be evaluated in terms other than itself. We were not witnessing a performance, but rather we were being asked to be part of the ceremony. Sure, we were sitting watching a stage, but in the intention of welcoming us, we were entering their land, their world view on their terms.

The time span of these stories, these oral histories and ceremonies force us to come to terms with our sense of time. How do we know that our sense of the present moment is the only one around? Other peoples may have a much larger sense of the present moment than we do. And the other way around. You know, if we were truly transcultural we would have to accept Australia’s original peoples’ story of their origin. The translation of Tjukurrpa as Dreamtime has in many ways devalued its significance to those whose idea of dreaming is nothing other than random – neurological – connections – sparking – off – in – the – brain – when – one – is – sleeping phenomena. The idea of a dream time in this context points to a time that is unreal, wispy as inconsequential jingles and daydreams. However, if we consider that Tjukurrpa may be as real in its own terms as cyber space is in the technological, we may have an entry into true and equal dialogue.

Whenever Western experts place their civilisation stethoscopes on Aboriginal artefacts and markings the dating goes further and further back into the mists of time. First the age of indigenous culture was put at 20,000 years , then to 40,000 years, then 100,000 years and currently as a controversial minimum 160,000 years before our present time. Perhaps its easier to accept their version of things. Kevin Bates worked next door to me as the Regional Aboriginal Coordinator at Newcastle Campus. One day I asked him how long did he think Aboriginal culture was around for. I thought that he might say 200,000 years or even longer. He said, “We’ve been here since the beginning of time.” I asked him if he meant that metaphorically. He replied, “What is it with you? It says what it means – we’ve been here since the beginning of time.”

During the Opening Plenary Session, Vincent Forrestor said,

” I want to make this clear. Many people think that native title only has to do with land. Native title is more than land, it is our heritage, our stories, our songs, our dances, our customs, our ceremonies, our language, our culture. In short, native title is our life.”

I was one of the many and now it was clear to me that treaties, agreements and other deals negotiated by non – indigenous ones are nothing short of bargaining for the spiritual, mental, emotional and physical survival of Aboriginal people. The dispossessed must bargain within the framework of the Invaders’ Law. It was only recently our courts admitted that when the invaders arrived there were humans here and that these humans had an intricate relationship with the land. The lie of terra nullius was corrected with the Mabo judgement. Now, a government that has big business interests at heart is trying to extinguish native title.

As I was walking out of the foyer I saw a poster of a man on a camel with a dialogue balloon saying, “Come camel riding in the Heart of Australia.” I remembered the little known history of the Afghani camel drivers who were especially invited to migrate to Australia about one hundred years ago. Their special skills were the husbanding of camels for use in Central Australia. Some returned to Afghanistan, some stayed and married Aboriginal women. The Islamic mosque in Alice Springs bears witness to the descendants of these Afghani camel masters. This brought to mind the Afghani writer, Idries Shah. In his introduction to the book, “The World of the Sufi”, by Ahmed Abdulla, Idries Shah mentions a story about Dhul’l-Nun the Egyptian and “The Pointing Finger Teaching System”.

In the surrounding lands, it was believed that a certain statue pointed to where hidden “treasure” lay buried. People from all over came to search, digging holes in areas indicated by the pointing finger of the statue. No one had found any “treasure” but still they searched heading further towards the horizon. One day, Dhul’l – Nun sat and watched the statue from sunrise to sunset. Then, on one particular day at one particular time, dug where the shadow of the finger fell, and discovered the treasure of ancient knowledge.

We need to turn around and not look at where the finger is pointing but to where its shadow falls. The finger points to never ending economic progress and development, it points to a future where the rich will only get richer at the expense of the poor. The shadow falls on native title. And the time is now. The Tjukurrpa – Dreamtime stories are the longest continuous religious beliefs documented anywhere in the world. (Josephine Flood, Archeology of the Dreamtime, Sydney and London, William Collins, 1983) Do we value the hidden treasure of the oldest living continuous culture on the planet? Do we recognise the “treasure” or do we filter out everything that requires some heart, some conscience? A natural sense of justice should spark a little recognition of the treasure in the finger’s shadow. The sense of a fair go cannot allow the extinguishment of native title.

While waiting for the bus to take us to Alice Springs High School, where most of the presentations were being held, I thought about the next few days. These few days will be an opportunity to step outside the routine of my ordinary life. Firstly, there will be four days of conferencing and then a few days of touring the Centre with some friends who are also LERNing.The fact is that just being in a different location had already disrupted my habitual comfort zone. To make the most of these days I would have to make an effort to turn inwards, so that the momentum of being in a different location and doing different things wouldn’t be wasted. The momentum, I hazarded a guess, is an energy or state of awareness that could loosely be called “holiday consciousness”. This turning inwards has nothing to do with solipsistic analysis and the chattering monkey mind trying to guess and to strategise the next moment. It is more the effort to intentionally steer one’s attention to other parts of one self normally unconscious. We may call it the subliminal underground of our being, the shadow, what we in the industrially developed world call only “feelings” and “sensations”.

It has been suggested that the human notion and definition of self has been through major shifts since the beginning of human consciousness (Julian Jaynes, “The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind”, Boston, Houghton Miffen, 1977 ). The closest to us historically, that may demonstrate this shift, is said to have occurred in Homer’s Greece.

According to this view, in Homer’s day, the people did not have the same sense of self as we may have. Their inner psychological organisation was different to what we take for granted. The voice of the mind was somehow perceived as a “god” speaking from outside themselves. It didn’t take too long before people started sussing out that there were a lot of “gods” running around in the temples and in the marketplaces saying contradictory things about how things were, that they saw the untruth of their “godhood”. Gradually this voice of the “gods” became established in the sense of self we call “ego”. What was there before the voice? Who and what was Ulysses’s “sense of self” on his Odyssey?

Have we in the dying years of the Industrial Age, come to a cultural cul-de-sac? Somehow, we have alienated ourselves from not only each other but also the common ground of experience – nature, the Earth. Is it time for another definition and sense of self, another way of knowing, one that acknowledges something other than the sovereign rights of the mechanistic, rational, technocratic and anti – spiritual mindset of the “Western” sense of self?

Edward de Bono in his “I Am Right, You Are Wrong”, thinks that this is the case. He suggests that a renaissance of thought and language patterns is needed so that humanity doesn’t self destruct. He proposes turning away from the “table top logic” of the traditional “Western” mindset in favour of developing a way of knowing that is based on perception. De Bono explains that recent developments in the understanding of self-organising systems and ideas from information theory, have given indications as to how the neural processes of the brain perform the activity of perception. Perception operates in nerve networks like a feature of a self-organising biological system, a living entity. Let’s call information that comes through our senses impressions. These impressions fall on the inner landscape of our mind like rain. The rain on the mind organises itself into tributaries, rivulets and streams of temporarily stable patterns. These patterns can subsequently flow into new sequences and patterns. According to de Bono, the perceptual mode of thinking encourages the mind to form multiple branching flow patterns; the sensory information is not boxed in by fixed linguistic concepts, generalities, and logic. Perceptual thought patterns follow the natural behaviour of neural networks; our present mode only plays back a recording of words and concepts provided by a preestablished cultural mindset.

Courtney Cazden during her paper on Ganma Space spoke of the necessity of getting rid of the margin and centre metaphor. This metaphor was based on the myth of terra nullius of students’ minds and being. Courtney told us that while she and Mary Kalantzis were flying to some school in the Northern Territory they noticed water holes that had fresh and salt water tributaries and other smaller rivulets all feeding the main space of the water hole. This, they found out was known as a ganma. The ganma looks like localised swirling spirals from the air. Courtney said that the mingling of brown, fresh and salt water in this space was analogous to the culturally diverse classroom. And in light of the process of perception is an apt image of the inner subjective world, our mind, our being.

The multicultural classroom as a Ganma Space, this metaphor rather than create separate marginalised groups besides the mainstream, recognises the primacy of all the diverse groups’ backgrounds and experiences. There is no one central dominant culture enforcing a mainstream reality. There is an influx of different cultures, different literacies, different world views, a swirling waterhole, a turning of bracken water whose salt has not lost its savour. A living Ganma Space.

Let’s go one step further and consider that in the industrially developed world there is the primacy of the head, (some localise it to the left hemisphere of the brain) and all the other ways of being and cognition – feelings, sensations and intuition have been marginalised. What do we have if we apply the ganma metaphor to our own inner world? In this ganma, head, heart, body and spirit all contribute equally, but differently, to our sense of the real. These parts of ourselves may all be cognitive in nature, they may be different tributaries of knowing, different source data. Ganma Space taken as psychological space, the internal world of our experience, would allow for the possibility to connect our known and unknown parts of ourselves. This opens the opportunity to connect with others by being able to include more of the “other” in one’s awareness.

Could the perceptual mode of thinking be a ganma way of knowing?

The taste I seek is a taste of being – not in the philosophical sense – a point of view to be debated, but rather an experience, an immersion through the background/underground of one’s chattering monkey mind – into the moment. We’ve seen that working from only a part of ourselves doesn’t work. The problems confronting all of us in this time of planetary transition are whole systems oriented. Now we see through Chaos theory, that a butterfly fluttering her wings in South Africa has global consequences. And when it comes to the ecological state of the Earth and the widening gap between the rich and poor across the planet, it is obvious that whole, global issues require an effort and a response that is from the whole of ourselves, the ganma of ourselves.

I decided to attend the presentation, “One Step Ahead: Aboriginal Perspectives on Management Education” by Evelyn Schaber and Second Year Management Training Program Students (Institute for Aboriginal Development, Alice Springs). As the classroom became full, with little standing room available, I was handed a printed page depicting in diagrammatic form Tjukurrpa and its sacred relationship with the people and the land. I was particularly taken by the fact that the primary relationship is a triad, a trinity.This trinity is reflected in Christianity, Hinduism, Taoism, Islam, Buddhism and other indigenous traditions. Joseph Campbell in his “The Hero With a Thousand Faces” and Mircea Eliade in his studies of religions and shamanistic traditions of the world point out other common features of invisible landscapes scattered across all cultures of the planet. So, what’s going on? What is this numerical coincidence that crystallises as a triad across and within all sacred traditions? Rather than be surprised by finding this fundamental triadic relationship within the sacred world view of the original people, I felt a kind of confirmation linked to feelings that arose during the Opening Ceremony.

After a few minutes, Evelyn introduced herself and the students beside her, Sherana, Patricia, Maxine, Cynthia and Sophie. She began by outlining the differences in the indigenous way of perceiving and knowing to the Western methodologies. She said, “It is not the knowledge that counts but how the knowledge is taught. Students need to know where the knowledge comes from and this must be put into political/ideological perspectives.” Evelyn explained that this entails the recognition of the narrative form, the story and the song as a valid means of conveying information and knowledge. Storytelling gives shape to knowledge and by having a whole form, bits of data and information find their meaningful place within the narrative. Evelyn compared the Western method of knowing to that of just focussing on a chorus and then a verse analysing each line of a song without knowing or listening to the whole song. “A song is more than the sum total of its parts. Our mob need to know the song, and hold the whole picture because education is political, education is an institution of the dominant culture. We need to be able to read where the dominant culture – ‘they’ – are coming from both politically and ideologically. That’s what is meant by having to be one step ahead.”

Martin Nakata, (University of South Australia) said at a later paper, Indigenous Perspectives on Multiliteracies , “Indigenous people must articulate their position, which has been historically constructed as the “other” and recognise the primacy of the indigenous perspective.” Martin also emphasised the importance of being taught by indigenous people, that what they had to say had as much verity as the dominant culture’s institutionalised knowledge. I was hearing that the indigenous way of knowing is holistic and the focus is on the whole song, the whole story. Martin was saying that there was an epistemological imperialism implicit in the way that research is conducted in “Western” institutions. I was hearing that an epistemology based on indigenous perspectives has as much ontological status as the positivistic technoscience paradigm of the “West”.

It just crossed my mind that the Greek word nomos, normally translated as law, as in eco-nomy, astro-nomy etc. can also be interpreted as melody or song. Eco – melody and astro – melody would give a different methodological approach to eco-law and astro-law, economy and astronomy. And who’s to say that the means of material exchange in traditional indigenous cultures is not more of an eco – melody than an economy? Perhaps the First Boat People and those who wish to take away native title didn’t and don’t wish to hear the songs of the original people, because their white noise mindset makes them tone deaf.

After Evelyn’s introduction and overview, each student began telling their individual stories of their personal experiences of formal education. I was witnessing a continuation of the welcoming ceremony and songs, this time in English, in a classroom. As each student told their story, of how they came to be doing the program and the various obstacles that were in their way to learning, I became aware of a soft uneasiness, a gentle tension in the air. As each student spoke in turn, I noticed in their bearing a vulnerability, an openness, an uncertain dropping of the guard. Their stories exposed their humanness, their heart. The how was more powerful than the what. The vulnerability and the innocence of that vulnerability began to resonate with a part of myself that could only respond in eyes welling up with tears. I told myself, “Big boys don’t cry in conferences….keep your act together….don’t make a fool of yourself….” The law and the wall of my persona, my sense of self, was being demolished by the truth of their song – stories. The tears trickled and I slowly turned my head to see all of the people standing behind me also crying. Indeed, by the time the last student had told us her story, I noticed that everybody in the class room felt the same way. Such openness, such vulnerability, such trust – such courage. Warriors of the Heart. The students’ eyes revealed the suffering and the strength that came through their own personal transformation. The sharing of their stories with us was a part of this transformative process and a political act. Smiles like chunks of sun beamed across their faces as we applauded and wept at the same time.

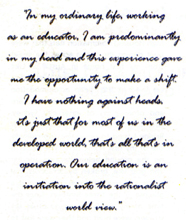

In my ordinary life, working as an educator, I am predominantly in my head and this experience gave me the opportunity to make a shift. I have nothing against heads, it’s just that for most of us in the developed world, that’s all that’s in operation. Our education is an initiation into the rationalist world view. This perspective lifts the intellect, the head, to a detached point of view that sees everything as if it is on the outside. It is called “objectivity”. When we teach our students literature, from this perspective, we tell them, “This story was written by someone, who was influenced by someone who was born somewhere”. Students learn facts, objective things that are apparently verifiable by reference to other someones who have written about the story or the author. The more one is initiated into the realm of the written word, and now also into the electrographic realm of cyber space, the less the realm of one’s own experience counts for anything in the classroom. Students learn facts about the story or the poem rather than the stories and the poems themselves. They learn that these facts are true because they are emotionless, they are detached from personal experience and work through the medium of the written word. Our classrooms devalue the spoken/oral tradition and value the written word. Our classrooms through our system’s methodologies enforce a monoliterate consensus reality.This reality is taught and is seen to be more valid than other ways of knowing, of communicating and of researching. In this classroom at Alice Springs High School, Evelyn’s students found a way to bridge the realm of the head with the realm of the heart through telling their stories.

I learned that I truly need to learn how to learn.

Perhaps this was heart knowledge – a grammar of the heart. We were in – formed through a literacy that was independent of our permission. The in – forming by passed our heads and touched our feelings. The soft uneasiness and the gentle tension in the air of the classroom transformed into a scent of the true. The ambience born from this exchange points to hope of true reconciliation – a sharing of a common ground – between the original ones and the rest of us, some place in the Heart of Australia. As Evelyn said, “We as educators have to confront and transform the realities of power in the classroom, and assist students to leave the baggage of 200 years of prejudice and discrimination at the door.”

This is what happened during the students’ presentation – intentionally or not, they directed our attention to include another part of ourselves. We had to acknowledge that there was more to each of us than meets the eye. And this more belonged to all of us in common. Ganma within, ganma without – turning, turning – ganma without, ganma within.

Is the phrase “language of the heart” just a metaphor? Do indigenous sacred world views point to a real place inaccessible to the chattering rational mind (with or without a PhD), but accessible to the intelligence of the heart? Does reflexive practice, with an intention to include more of one’s self than just the head, allow for the entry of compassion? By doing this as educators, could we be assisting in creating textual bridges through firstly becoming human bridges? Are we talking about the politics of consciousness and the need to question the root assumptions of “Western” techno – rationalism? Do these assumptions, these desacralised paradigms of reality only make it possible to see a sacred site as a potential dollar making or military site? Was Kevin Bates right when he said that the Aboriginal people have been here since the beginning of time?

The act of turning inwards and acknowledging the ganma of one’s being is a political act of consciousness. This act may only be for a fleeting moment but it may have long term consequences in the classroom and the community. How does one move far enough away from the chattering rational mind, “table top logic” to include the stirring of feelings and sensations, without in any way losing the attention required to participate in events around one? Who is moving away, and where is this away? Who am I? Why am I here? These questions, if I can keep alive their intent, may open doors to other literacies that resonate through different cognitive frameworks underpin the creation of other worlds. These questions, this search for inclusion in the whole by becoming more whole may be the first letters of an unknown alphabet within my own being.

At the end of a day’s attending papers I decided to go on a guided tour of a sacred site. The promotional poster had this to say :

“Native Title Rights, Educational Rights” – A Time Line Presentation,

presented by Vincent Forrester.

Experience a Tour to Kyunba (Native Pine Gap)

– sacred site – 20 kms south of Alice Springs.

Institute for Aboriginal Development, Alice Springs.While driving to our destination, our guide Vincent Forrester, called out the names of the surrounding hills, rocks and dirt and told us the stories of their birth. In this named landscape I was an alien. The naming stories revealed an invisible landscape that is visible to Vincent and his people. As we got off the mini – bus, Vincent said, “Welcome to my country”. Was I really in his country? Just because I was physically there, standing on the dirt, didn’t necessarily mean I was inhabiting the same sense of place.

The sense of country that gives birth to the Tjukurrpa – Dreamtime stories must be completely different to that which just measures acres of dirt. Somehow I was locked out of a sense of country and a way of knowing that Big Bill Neidjie, a Kakadu Aborigine refers to:

“I feel it with my body, with my blood. Feeling all these trees, all this country…when the wind blows you can feel it. You can look, but feeling…that put you out there in open space.” (Quoted in James Lowan, “Mysteries of the Dreaming” )

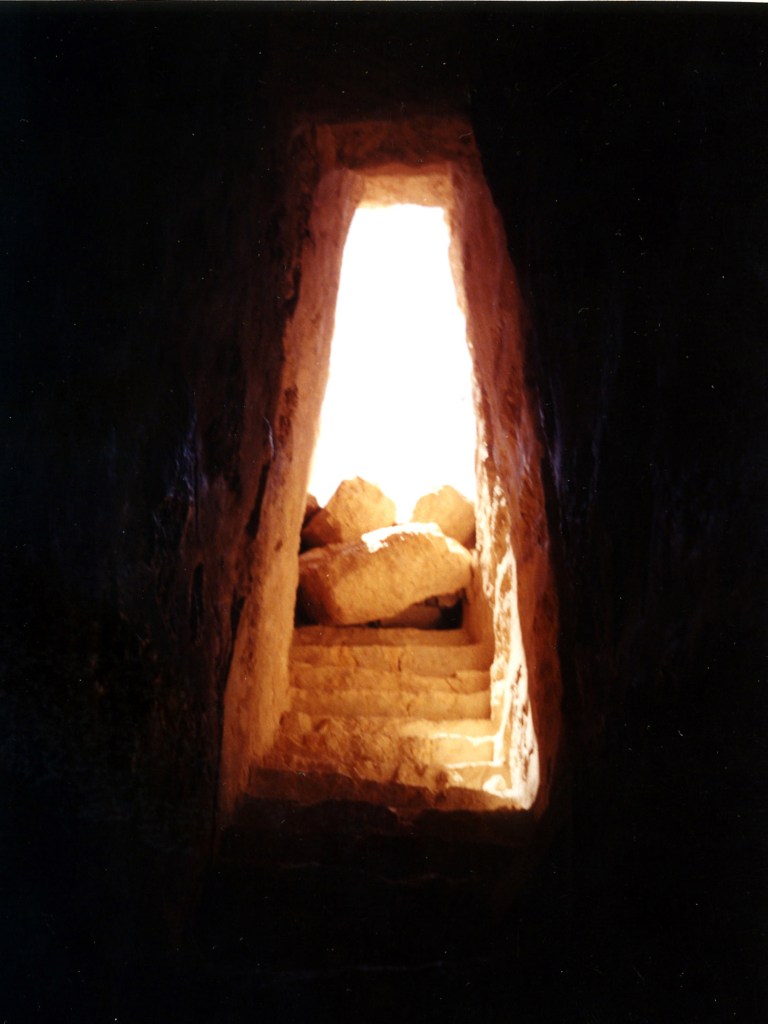

As the sun was setting, we walked following Vincent, he pointing out the various plants that had medicinal and other uses, we in silent curiosity and wonder. He showed us the places where adolescent males had their initiation rites. There were rock carvings and paintings at one ceremonial spot that seemed to have grown from out of the rock assisted by human hands. Vincent told us that some visitor had chipped off and stolen a big section of the painting/carving. It left a sharp straight line where it was separated from the greater stone and a large hole. No doubt, the missing stolen piece was going to be placed on a mantle shelf as a decorative item probably besides some bric – a – brac. Turning, he pointed his finger towards some low lying hills where the women had their own initiation ceremonies and rites. Ahead of us, about five minutes walk away, was the sacred centre of this land. We were not allowed to go there.

As we were returning to the mini-bus, the red colours of the twilight and the trees’ silhouettes shimmering in the breeze made me feel as in a dream. Pointing to a thin line, a wire fence nearby, Vincent said, “Our next door neighbour, over this fence, is Bill Clinton. In the 1960s, Prime Minister Harold Holt gave this land to the President of the USA. He didn’t talk to us, he didn’t ask us and he didn’t charge the USA any money. He just gave our land to President LBJ. This place over the wire fence is Pine Gap, a military site, where not even white Australians are allowed to visit.”

By now it was dark, with only the head lights of the bus providing some illumination. Just as he was about to climb on the bus, Vincent paused. There was silence for a few seconds as we waited. With a slight quiver in his voice, he said,

“I am asking you educators, you teachers to do something. We could sell land worth seven and a half million dollars to Woolworths for them to build their shop in Alice Springs – but there’s none of our children working there. Our kids are leaving school in year 8 and don’t return. You, you people who are the educators must do something.”

We boarded the bus and as I looked through the bus window I noticed the stars and the pattern we call the Southern Cross. Thoughts and feelings were stirring inside of me. Vincent was pleading with us to find a way to make education accessible to his people. He wanted his people to be initiated into the realm of literacy that confers power in the “Western” sense. Pine Gap – that “secret” electronic spy installation for the military purposes of Pan Americana, was just over the fence from a sacred Aboriginal site. He wanted his people to be able to straddle two realms – that of the Tjukurrpa, a sacred perspective and that of the “West”. The ability to do this is dependent on native title rights and educational rights for the original people of this country. The ability to straddle the two realms, the two world views, may also be essential for us to ensure the survival of all of us and the planet.

The Pine Gap military site is part of the electrographic world that now envelopes the globe. This electrographic world has connected all continents and carries data on every square inch of the earth’s surface traced by geostationary satellites. Information from the furthest reaches of the solar system and further out through Hubble’s eye, swirls into it. We are now immersed in an electrographic mist of data. Over the next 20 years or so, the mist will become rain, and this rain may become a flood of data. Or, it may become a global informational ganma. It all depends on us and the new neural networks, modelled on the human brain, that are now being developed.

The current digital infotronic revolution could have an impact on humans to rival the impact that the arrival of language had on the dawn humans. It is possible that the 40 year period between 1980 (the arrival of the Personal Computer) and 2020 may be seen in hundreds of years time, as one of the greatest turning points in human history. This revolution is much larger and faster than previous transitions like the change from an Agrarian Age to the Industrial Age. Whereas before, transitions occurred in specific places and gradually spread across the globe, the current revolution in technology is being felt globally and almost instantaneously. Through the coming Digital Age a global culture is emerging.

What must it have felt like about five hundred years ago when the very first book was published on a printing press? For one thing, Gutenberg probably didn’t foresee that literacy skills would be needed by everyone. Today it is seen as a fundamental human right. Five hundred years ago only a certain elite, members of the church and some others, had access to books which had been hand copied one by one by monks. They were the only ones who could read and write. Gutenberg democratised the need for literacy. In the new world order of the Digital Age many people may not be able to access information technology and may not have the necessary electrographic literacy. This means that the poorest will become even poorer without access to this technology.

Questions and concerns like these were fluttering around in my head when I first met Johan Cedergren at the Dingo Cafe, Alice Springs. Johan, a teacher from Rodengymnasium Upper Secondary School, Sweden came to present his paper, “Baltic Region Knowledge: An Interdisciplinary High School Course for Swedish and Russian Students”. This project is part of a long term program for re-establishing contacts between north western Russia and the new Baltic States. The internet is used extensively to network the students between the two countries.

I also had an interest in this new technology and my paper, “The Hunter Connection: Getting Ethnic Communities Online “ was on a rural strategy that the Multicultural Education Unit, Hunter Institute of Technology, Australia is implementing to address the local community’s communications needs.

Johan and I found that our concerns were similar. How do we ensure that this technology is accessible to all who need it? The small proportion of humanity who has access to this knowledge and technology also uses up most of the planet’s resources while the greater majority of humanity is undernourished and living in poverty. This small proportion of humanity, from previous experience, may build new virtual ivory towers far removed from the hoi polloi paralyzed by techno fear or by the lack of access to the technology. There is a need for groups that have been “marginalised as the other” to colonise Cyberia. The secular clergy of our small proportion must work to ensure that all have access.

Whatever the answers to these issues, the fact is that we are experiencing a fracturing of the idea of specific location in space. Telecommunications in all its diversity is bringing the globe to one’s home and one’s home to the globe. Video conferencing in virtual rooms with participants from all over the world are a reality now. I cut and pasted this information about the Tanami Project from some email message I received in 1996:

VIDEOCONFERENCING IN THE OUTBACKSince 1993, Aborigine communities in Australia’s Northern Territory have

been using videoconferencing as the primary medium for personal and business communications among each other and other sites in Sydney, Darwin and Alice Springs. The Tanami Network, which uses PictureTel videoconferencing equipment, is favored over the telephone or radio because it can convey the extensive system of hand gestures used by aborigines while speaking. Most of the videoconferences held are personal or ceremonial in nature — paid for in large part by mineral royalties and community funds. Other aborigine videoconferencing networks include the Mungindi Project, which uses Cornell University’s CU-SeeMe software to link four remote schools.

(Technology Review Apr 96 p17)

This multimedia technology makes it possible to communicate Tjukurrpa information to community members whether three hundred kilometres or three thousand kilometres away. It is possible, with the right intent, to straddle both “Western” and indigenous perspectives if the technology is used appropriately and the resources accessible.

Both Johan and I decided to go and see this project. Johan went on a bus with a group of other LERNers to Yuendumu about three hundred kilometres from Alice Springs on the edge of the Tanami Desert. I went with another group to Alice Springs. When we became connected, the information signals were beamed to Sydney then bounced off from a satellite to Alice Springs and Yuendumu. It was a strange sensation communicating with this technology, there was a slight adjustment required in one’s sense of place. The next day in the foyer of the Araluen Arts Centre, Johan asked me to have a look at his laptop computer. On the screen was a picture of myself taken from the video screen at Yuendumu. Unknown to me, Johan took a picture of me “hosting” on his digital camera. He showed me other pictures he took of the conference. These pictures I downloaded from his website in Sweden when I returned home to Morpeth, NSW.

So, digital images taken from an electrographic encounter in the centre of Australia are accessible to anyone, anywhere in the world with the appropriate technology. Not only images but also sound and text.The possibilities of using this technology to enhance communications between all of us is immense. The tributaries of information are now global and the challenge for us, as educators, is to ensure that all have access.

Those who do have access to the infotronic labyrinth with walls of World Wide Webs, do we need a thread like Theseus received from Ariadne to find our way to the centre and back? Who is the monster at the centre and what is the thread? Unlike geographical Siberia, Cyberia resides in non-Euclidean space where North, South, East and West do not exist. So, where is the centre of the maze? A computer program is a set of linear binary instructions. There are as yet no computer based devices which can handle patterns. Stories, as information devices, handle and convey patterns of knowledge.

Perhaps the thread we seek is our own story making capacity.

The four days came to an end too quickly. The Closing Ceremony was performed by Pitjantjatjara traditional dancers. Faces of people I had met, the garden chats, the painting of the Conference Mural by LERNers, images of the management students, the Conference Dinner when we let our guards down and saw each other in motion, floated through my mind during the asymmetrical pauses of the dancers. A performance by a group of young local people followed giving the other half of the Closing Ceremony. The emerging global culture and its expression were clearly seen in the dancing. Dancing to contemporary hip hop music with moves informed by their aboriginal inheritance, the group expressed movements that were both uniquely local and global at the same time. Ganma dancing?

The next day I met up with my touring companions to pick up the hire car. All of us were born in different countries and had made Australia our home. Alejandra Martinez from Chile, Chandrima Mukerjee from India, Jenny Howard from Borneo, Beatrice Espenez- Stotz from Uruguay and myself from Greece. Our car was a little ganma space on four wheels, touring the centre of Australia with five dinkum Aussies. Alejandra, was the holy of holies – a mother to be, with only three months to go before the birth of her baby. I felt that her presence would ensure a safe passage for us all. Once we picked up the car I took some tapes out of my bag which would become some of the soundtrack of the trip. The first song we listened to as we were leaving Alice Springs was “Two Way Dreamtime” by Directions in Groove (DIG). We played this song often at different points on our journey :

Two Way Dreamtime

Dreamtime on a leyline, forty thousand years is a long, long

Dreamtime on a songline, forty thousand years is a long, long

Dreamtime on a leyline, forty thousand years is a long, long

Dreamtime on a songline, forty thousand years is a long, long time.

Welcome to the alien nation, and this society based on invasion

where we don’t know soul from a hole in the ground.

Two hundred years of beating around the bush, digging money out boom or bust, well, ashes to ashes dust to dust…

It’s all those people that you buy and sell, millions of shares in a living hell. You’ve got a house and a pool and a Porsche and a beeper, but are you just making life cheaper, you’re gonna have to dig a little bit deeper, the price of admission is so much steeper.

You pay with your dreams, so wake up sleeper.

Dreamtime on a songline, forty thousand years is a long, long time….

Welcome to the alien nation, but it’s not too late to change the equation.

Listen to the A-B-original people, the Earth is a church without a steeple, don’t look for heaven in a father above, it’s here on the ground in a family of love and deeper respect for each other, brothers and sisters with the one Earth for mother.

Now life is a state of constant creation and what we need is inspiration.

There’s more to me than meets the eye, so let’s find the spirit that let’s us try, to make a treaty with the past or we’re doomed to a future that cannot last. Heal the wounds, confess our crimes, free at last in a two way dreamtime….

Directions in Groove

The first place we visited was Stanley’s Chasm, a huge gap at the tail end of the McDonnell Ranges. We walked up and through a stony path, past desert palms, mulga, a plant with flowers smelling like delicate lavender. We saw a couple of rock wallabies scurry up shear vertical rock faces. We entered the chasm and heard frogs croaking. The rain had brought the mating calls of the frogs that reverberated through the chasm. As we walked out I had the distinct feeling of having emerged with realigned impressions. The surrounding rocks and trees vibrated invisibly and silently. Ally laid on her back across a flat smooth striated rock. Her belly, full of new life made a silhouette just left of Stanley Chasm’s opening . Birds became audible. Ally spoke to Beatrice in Spanish. I asked them what they were talking about. They said that they both felt as if they had just emerged from a womb. The words Mother : Matrix : Matter rose to the surface of my mind.

Space is what you first notice, once you’ve travelled in Central Australia a few hundred kilometres on no speed limit roads. The massive road trains, when they appeared, shuddered a reminder of how small you and your car really are. The expanse of sky and the horizon of the world’s most sparsely populated lands (apart from Antarctica) made me feel my smallness. Our first stop for the night was at King’s Canyon.

Late at night I walked along an elevated metal path that was built to conserve the local environment. I was going to view the profile of King’s Canyon against the night sky. The end of the path was about half a kilometre away from the cabins. While walking down the metallic path, my footsteps echoed through the night space. Finally I stood at the end of the “Western” metallic thread. I turned towards the cool breeze blowing through the native land. How far had this wind travelled to get here – the Centre of Australia? Across hundreds, perhaps thousands of kilometres of ground that was almost empty of people. I looked at the Milky Way splashing across the dome of my mind, streaks of falling stars crossed above King’s Canyon. All the while I felt the Southern Cross watching over us.

The next day after seeing and walking around King’s Canyon we headed further south to Uluru and Katajuta. Twenty five years ago when I arrived at Erldunda, the turn off to Ayer’s Rock and the Olgas, I couldn’t take the turn and went direct to Adelaide. This time I was ready.

On the way to Uluru we passed Atila (Mount Conner) whose flat table top contrasted with our post card expectations of Uluru’s and Katajuta’s roundness. We were only about twenty kilometres from Uluru when we passed an old panel van crowded with local Aboriginal men, women and children, waving to us. Getting closer to Uluru, the following refrain came from the car’s radio:

What if God was one of us,

just a slob like one of us,

just a stranger on the bus

trying to make his way home…..In the near distance we caught a glimpse of Uluru, the largest Rock on Earth, right in the Centre of Australia, now in front of us. With many other vehicles we parked at the specified viewing area. We had arrived at the most opportune time to witness the almost miraculous changes in colour of Uluru as the sun sets. Uluru turned our sight away from the west where the sun was setting, towards the Red Centre. The shifting reds of the Rock vibrated against an eastern blue sky, the shadows of mulgas nearby almost merged with the red dirt.

The next day we visited Uluru where we spent some time at the Cultural Centre. Along the inner walls of the Centre, a Dreamtime story written in English had Aboriginal paintings as iconic reflections. The version below of the same Kuniya story comes from “Uluru, an Aboriginal History of Ayers Rock” by Robert Layton.

The Kuniya story (The Pythons)The Kuniya converged on Uluru from three directions. One group came westward from Waltanta (the present site of Erldunda homestead), and Paku-paku; another came south through Wilpiya (Wilhia Well); and a third, northwards, from the area of Yunanpa (Mitchell’s Knob). One of the Kuniya women carried her eggs on her head, using a manguri (grass head-pad) to cushion them. She buried these eggs at the eastern end of Uluru. While they were camped at Uluru, the Kuniya were attacked by a party of Liru (poisonous snake) warriors. The Liru had journeyed along the southern flank of the Petermann Ranges from beyond Wangkari (Gills Pinnacle).

At Alyurungu, on the southwest face of Uluru, are pock marks in the rock, the scars left by the warriors’ spears; two black-stained watercourses are the transformed bodies of two Liru. The fight centred on Mutitjulu (Maggie’s Spring). Here a Kuniya woman fought using her wana; her features are preserved in the eastern face of the gorge. The features of the Liru warrior she attacked can be seen in the western face, where his eye, head wounds (transformed into vertical cracks), and severed nose form part of the cliff.

Above Mutitjulu is Uluru rock hole. This is the home of a Kuniya who releases the water into Mutitjulu. If the flow stops during drought, the snake can be dislodged by standing at Mutitjulu and calling ‘Kuka! Kuka! Kuka!’ (Meat! Meat! Meal!). The journey to Uluru and lhe Liru snakes’ attack are described in the public song cycle recording the Kuniya story.

Almost half way along the Cultural Centre’s inner wall, a large video screen was showing the same traditional dancers that had performed the Closing Ceremony at Araluen Arts Centre. An electrographic video echo in Uluru.

When we approached Uluru none of us could envisage climbing the Rock. The original people of this land plead with tourists at the Cultural Centre not to climb Uluru. Even at the site where a chain railing extended up a ridge began its climb, there was a sign with a Red Cross stating that the local people would strongly prefer people not to climb Uluru because it was against their religious beliefs. Again, it was a request. What do fellow humans have to do to at least elicit some semblance of respect for their beliefs?

I am reminded of the Sufi saying: “When a thief sees a saint, all he sees is his pocket.” In this context could it be, “When a fool sees a sacred site, all he sees is a ladder of chains.” ?

On the way back to Alice Springs we decided to stay the night at Erldunda and make an early start the next morning. Once we got to the turn off I rang my family and found out that a friend had died the night before. Returning to our table outside the roadhouse, in shock over the news, I wept. My travelling companions brought coffee and sat with me. Their company was a comfort.

A group of about six Aboriginal men were dropped off a utility truck a few metres away from us, while I was lighting a cigarette. Speaking their native language they sat and stood a few tables away from us. One of them, who was standing, caught my eye and looked at me for as long as it takes to inhale and exhale two complete breaths. He walked over to our table and it was clear by the way he asked for a cigarette that English was his second language. I gave him the pack and the coffee with the news of Kevin Bates’ passing away resonating through my heart. He sat with us for a short time. An echo from twenty five years ago was heard at Erldunda that night. Twenty five years before, the old man had given me milk, biscuits and shelter somewhere near here. Twenty five years later I had given in return, acquired habits. Somehow, it didn’t feel it was an equal exchange. Somehow, I felt that I was still in debt.

After a while the utility truck returned to pick the men up. As they left I wondered at the coincidence of place, time and events. I meandered to my cabin, noting that the only other time I slept in Erldunda was in a humpy by the side of this road. Having said good night to my companions, I sat outside trying to locate the Southern Cross. I noticed a swarm of fireflies swirling to my right near a gigantic eucalyptus tree. I stared at the fireflies remembering that they are sometimes a symbol of the soul’s ongoing life after death.

Ally bought “Tribal Voice” by Yothu Yindi as soon as we arrived at Alice Springs. She wanted to ensure that the last musical sounds we listened to as we drove our hire car to the airport came from this part of Australia. Driving to the airport we heard the song :

TreatyWell I heard it on the radio – And I saw it on the television – Back in 1988 – all those talking politicians – Words are easy, words are cheap – Much cheaper than our priceless land – But promises can disappear – Just like writing in the sand – Treaty Yeh Treaty Now Treaty Yeh Treaty Now – Nhima Djat’pangarri nhima walangwalang – Nhe Djat’payatpa nhima gaya nhe – Matjini Yakarray – Nhe Djat’pa nhe walang – Gumarrt Jararrk Gutjuk – This land was never given up – This land was never bought and sold – The planting of the Union Jack – Never changed our law at all – Now two rivers run their course – Separated for so long – I’m dreaming of a brighter day – When the waters will be one – Treaty Yeh Treaty Now Treaty Yeh Treaty Now Treaty Yeh Treaty Now Treaty Yeh Treaty Now – Nehma Gayakaya nhe gayanhe matjini walangwalang nhe ya – Nhima djatpa nhe walang – Gumurrtjararrk Yawirnny – Nhe gaya nhe matjini – Gaya nhe matjini – Gaya gaya nhe gaya nhe – Matjini walangwalang – Nhema djat’pa nhe walang – Nhe gumurrtjarrk nhe ya – Promises – Disappear – Priceless land – Destiny – Well I heard it on the radio – And I saw it on the television – But promises can be broken – Just like writing in the sand – Treaty Yeh Treaty Now Treaty Yeh Treaty Now Treaty Yeh Treaty Now Treaty Yeh Treaty Now – Treaty Ma – Treaty Yeh – Treaty.

(M. Yunupingu / G Yunupingu / M Mununggurri / W Marika / S Kellaway / C Williams / P Kelly / P Garrett)

While flying over the Simpson Desert on the return journey, I thought about Gracelyn Smallwood’s paper where she compared the state of South Africa’s original people and Australia’s. She said,

“South Africa is striving for Truth and Reconciliation, not just Reconciliation without Truth. The truth is that over three quarters of the Aboriginal people have been murdered over the last two hundred years in Australia. In South Africa, the blacks during apartheid, kept their language and culture. In Australia there is a selective amnesia operating when it comes to the indigenous people. We need both Truth and Reconciliation.”

Perhaps one of the consequences of working towards Truth and Reconciliation may be Justice for the original people of this country.

I noticed that the land was getting greener and soon we were flying over the Great Dividing Range. Though I looked, I knew that I wouldn’t be able to spot the Three Sisters rock formation of the Blue Mountains. I was hoping that as we curved our landing onto Sydney Airport I’d catch a glimpse of what I and my two brothers called the Three Brothers. These were three twenty storey high Housing Commission flats that were built during the sixties across the street from my first home in Australia. Like many migrants of the fifties and sixties we lived in the cheap accommodation that was available those days in Redfern and other parts of inner city Sydney. Orienting my gaze from Sydney Harbour Bridge I tried to guess the approximate site of my first home here. The patterns on the ground below became angular and grid like, broken by the occasional patch and oval of green. I didn’t get a glimpse of the Three Brothers. Since the time of my childhood, many other sky scrapers were built and they were lost to me.

Botany Bay came into view as our plane was turning to land. As our plane looked like it was going to touch the water I felt Sydney, Eora, an edge metropolis of our ganma continent turn around the Red Centre, the rocks, hills, mulga, spinifex, red dirt and a few people in the Heart of Australia.

Published in Education Australia,1998

Posted by stavr0s

Posted by stavr0s