I know this is unusual for a writer to post a draft of a first chapter of a book they are writing. As those who write know, writing is lonely. I’m about 3/4 of the way through with the first draft of my book and I have no idea how it will be received. It is based on my trip to Turkey looking for people who knew or are related to my grandparents who were Pontic Greek refugees during the holocaust in Turkey in the 1920’s. Let me know what you think in the comments area. By the way – Papou means grandfather and Yiayia means grandmother in Greek.

====================================================

“You can’t go there! You’d be crazy to go,” he grabbed the towel on the chair and wiped his face, “This is not Australia; this is Greece, and you want to go to the village where your family was massacred in Turkey!” He cocked his eyebrow and wiped the corner of his mouth with his finger. We were in the kitchen. Light streamed through the window, leaving a vivid white patch on the tablecloth.

He leaned towards me with specks of sawdust in his hair. He said,

“Why go there? You can have a holiday anywhere but want to go to Bafra. Do you know how far it’s from Constantinople?”

His singlet was sweaty, and his boots and pants were spattered with cement. He sat on the fruit box, tugged at his shoes, and placed them beside the broom.

How do I explain my motives to Taki? I flew from Australia, and now, after over 40 years, I am back in my birthplace, Yannina, Greece. I wasn’t always going to be so late returning to where I was born, but raising kids and lacking money meant I couldn’t go. My father’s death made it possible for me to return from the Great Southern Land to Greece. I was a late prodigal son, now a stranger and not a son.

We migrated from Greece when I was four years old. All my memories and pictures are of a child – rolling down a hill, the log bridge I crawled across so small and scared, stuffing olive seeds down holes in the floor. My father’s recent death shocked me into looking at my life. The hourglass sand days and moments flipped over. Thoughts were framed with death, the fence around life. But after that, what? I couldn’t think of a better place to be than on the Holy Mountain celebrating Easter with these and other questions, breaking bread with monks.

“Look, I understand…..you don’t want me to get hurt,” I said

“Hurt! That’s what you call it. Hurt? I don’t want you killed! Are you stupid or what? If you go to Bafra, my dear cousin, you will either be killed or bashed to a pulp. Same thing. It’s that simple.”

He knew that as a fact.

I meticulously planned my journey from my home in Sydney over many years, studying a world map. My gaze lingered over Asia Minor and Greece, retracing the paths of my ancestry, both in blood and spirit. Countless times, my finger traced along this route. First, it pressed upon Athens, then Patras, followed by Yannina, and further to the Holy Mountain. From there, finger by finger, it went towards Turkey, Syria, Jordan, Israel, Mount Sinai, Cairo, and back to Athens for my return. Later, I would repeat this ritual on the computer, using a cursor and a click to delve into the two-dimensional world of maps. It was a voyage of dreams, one I had envisioned for years.

Upon learning that my mother was the child of refugees, the desire to visit the land from which my grandparents had escaped grew within me. I was born in Greece to a Pontic Greek mother and a mainland Greek father. My mother seldom spoke of her heritage, save for a few passing remarks, like, “If you think Aboriginal people are mistreated, you should have seen how we were treated in Greece!” Whenever I asked her to elaborate, she would sidestep the question. Thus, I lacked a label for my identity for the longest time — I was Greek. That was it. Until much later, I discovered I was a Pontic Greek because my mother was Pontian.

After migrating to Australia, I never had the chance to see my grandparents again. We departed Greece when I was four years old. While my father’s parents perished at the hands of the Nazis during World War II, my mother’s parents were alive when I came into this world. Turkish was the initial language that enveloped me from birth until age four. I learned this recently. My mother informed me that the Greek government had made it illegal for Greek refugees from Turkey to speak Turkish, insisting they only use Greek. It must have been a challenge if they didn’t know the language. Nevertheless, in the village of my birth, predominantly inhabited by refugees from Turkey, Turkish was spoken within the confines of the home, only giving way to Greek when outsiders visited.

So, why were there Greek refugees from Turkey? My mother never disclosed the details. Even my father remained silent on the matter. Thus, I knew nothing about the Greek Holocaust until much later in life. My mother either didn’t wish to divulge the information or was unaware. As the youngest, she wasn’t born when my grandparents fled Turkey.

“Taki, I simply want to look at the village where our grandparents resided before they were forced to flee Turkey. It’s been over 80 years since that happened! I yearn to find someone who knew them. Everyone in our family perished in Turkey, except for our grandparents. I’m curious to witness that place. I never had the opportunity to know my grandparents as you have. My parents whisked me away to Australia when I was a mere four years old. I spent my days on the opposite side of the planet, growing up and becoming a father. This morning, I finally visited Papou’s and Yiayia’s graves. And that’s precisely why I’m bound for Bafra—to connect with my ancestral roots.”

I couldn’t reveal to him that my journey harboured other destinations and motives, such as Konya in Anatolia, where I wished to pay homage to Rumi, the Sufi saint. I feared that if I disclosed this, he would utterly panic and misconstrue my intentions. In his eyes, being Greek equated to being an Orthodox Christian, and displaying any interest in Islam aroused suspicion. It pressed all the wrong buttons.

“Ah, Stavro, you think like an Australian, but history intertwines whether you like it here. One glimpse of you, and they’ll recognize you as a Greek. Then, that’s it…you become a marked man.”

I took a seat at the table, the coffee still steaming. Taki settled across from me. “What’s this? I’ve toiled all day under the scorching sun, constructing a chicken shed, and you haven’t offered me a cup of coffee!” He grinned.

I poured him a coffee. His slender hand clasped the small, white cup while his other hand gently tapped the tablecloth in rhythm with the melodies wafting from the adjacent lounge room.

“So, is this the reason you have yet to embark on your journey to Bafra to see the homeland of our grandparents? It’s just a few days away by train and bus, yet you haven’t set foot there? I find it hard to believe that you lack the curiosity to see where they came from.”

“That’s the thing. Turks in Constantinople are tolerable; they’re city folks. But beyond the city, in the small towns and villages, Greeks face peril. Bafra, a small town on the Black Sea coast, lies over a thousand miles from the city. You don’t speak Turkish, and you can’t disguise the fact that you’re Greek. I don’t know if they still rely on donkeys and horses for transportation. You’re venturing into history, into suffering, into genocide. It’s perilous for a Greek, and there won’t be any tourists or travellers because there’s nothing to entice them. So, you’ll be on your own. Anything could befall you—imprisonment, remember the movie ‘Midnight Express’? And no one will come to your aid. I can’t think of anything more foolish than spending your vacation on that.”

“You forget one thing—I’m Australian. That’s what my passport says. Even if I don’t meet anyone, at least I can return to Australia with a collection of photographs depicting the area. Honestly, Taki, I believe you worry too much,” I remarked.

“How do you expect to find someone connected to our grandparents? You don’t have an address, you can’t speak Turkish, and no soul speaks English or Greek where you’re heading. You’re a Christian, they’re Muslim—remember, their ancestors massacred Greeks and Armenians by the millions. You do not understand what you’re getting yourself into, and I can’t bear the thought of not warning you.”

“I won’t be undertaking this journey alone.”

“What do you mean? Who’s accompanying you?”

“Well, I’ll depart for Easter for the Holy Mountain in a few days. Being there will guide me to someone who knew our grandparents, even if I can’t speak Turkish.”

“What? Will praying alongside monks in a monastery assist you in achieving your goal? Are you serious? You’re out of your mind. I had no idea you were a religious man.”

“I’m not religious if you measure it by church attendance. Besides, I had planned to visit the Holy Mountain with my father before he passed away, and now seems like the perfect time to fulfil his wish. I believe that extraordinary things can happen, and since I only have myself, why not seek the support of others who may aid me in some way? I believe that merely being on the Holy Mountain for Easter will help my desire come to fruition.”

“I don’t understand you. You’re an educated man—the first in our family to obtain a university degree. You use computers and hold a respectable job with great responsibility in Australia. How can you believe in superstitious nonsense like God, prayer, and the notion that Mount Athos and its monks hold any value? How can monks on a mountaintop in Greece assist you in Turkey? These are the things peasants or,” he widened his eyes, “madmen believe in!”

While I wasn’t a regular churchgoer, the word ‘pilgrim’ resonated with me more than ‘tourist.’ Pilgrims embark on a personal quest for truth regardless of faith or belief. I sought truth, and I craved tangible evidence of that truth. Was I a sceptical pilgrim? Was I a doubting Thomas with time on his hands?

“Have you ever been to the Holy Mountain?” I inquired.

“No, and I never will set foot there. If I ever do visit, it’ll be a day trip as part of a tourist group—take some videos, snap a few photos, and maybe buy a souvenir. But there’s no way I’ll ever spend the night and sleep there.”

“Why is that?”

“It’s those monks. They possess powers—they can see right through you. I’ve heard that once you converse with a monk from Mount Athos, they see your lies. You know, as if they have X-ray vision into your soul.”

“The X-ray eye? I’ve heard of the evil eye, but is that its reverse? You’re afraid of something you don’t even believe in.”

“Just because they possess powers doesn’t mean they converse with angels and grapple with demons. They are formidable men, and I don’t want any man peering into my soul,” he said.

“So, you’re suggesting their powers don’t come from God?”

“Nor the Devil.”

“Then where do they come from, if not God or the Devil?”

“They emanate from within themselves. How would I know? Look, there’s no way I would go to Mount Athos or Bafra. I can’t fathom your mind. You’d rather visit a monastery than Mykonos and its discos. And you’re alone—your wife is on the other side of the world—you’re on vacation. Enjoy yourself! You don’t even have a video camera! Being from Australia, everyone expects you to have money… You do have money, don’t you?”

“I have enough for my journey and to return to Australia.”

I displayed my discount watch from the supermarket. I pulled my inexpensive snap camera from my shoulder bag on the chair. “I don’t want to fret over possessions while I’m on the move. Besides, who would want to steal my watch or camera?” I chuckled.

“So, you’ve got it all figured out, huh? You want to be invisible, just like the common folks. Well, good luck with that,” he laughed.

He rose to freshen up and change.

“Tomorrow, I’ll be your tour guide. I want to take you to a special place—a wax museum showcasing the history between us and the Turks, created by the renowned Greek sculptor Pavlos Vrallis. The real history. You’ll see wax figures dressed as your grandfather and grandmother did when they arrived in 1922.”

“You know, I was in Constantinople a few months ago.”

“What? How was it?”

“Turkey was ravaged during the massive earthquake in 1999, just like Greece, but the Turks suffered even more. Many Greeks went over to lend a hand. What do you do when you witness 100,000 people perish next door? But sharing this doesn’t mean I share your enthusiasm for going to Bafra. I told you, a big city, a big heart— a small village, a small heart.”

“That’s nonsense. Do you realize we’re in a small town right now? Does that mean everyone here has a small heart? What about those monks with powers residing on an isolated mountaintop—do they possess small hearts? Do you believe that New York and London people have the biggest hearts?”

“You seem to have all the answers. Later, I’ll take you to my workshop. I want to show you some silverware I’ve been working on. I’m crafting the Passion of Christ in bronze for the local church.”

“You’re full of contradictions. You don’t believe in God and consider religious people foolish, yet you’re sculpting the life of Christ in bronze for a church!”

“There’s no contradiction. Priests want that image, and they pay me, and I make my living. I’ve been asked to make all sorts of designs by all sorts of people. To me, they’re all the same – paying customers. The local priest wants that design, and I give it to him for a price. It’s that simple. It puts bread on my table. So, yes, I suppose I can thank God for that!”

“Ah, Stavro! How good it is to see you this morning, to hug you!” she said, “I remember you as a baby. The last time I saw you was before you left for Australia. You crawled on the floor, picked up crumbs, and put them in your mouth. Along with the crumbs, you picked up some dirt. As you ate the bread, the dirt became mud, dribbling down the side of your mouth. Soon all your mouth was covered in mud!” She laughed between the tears. Yes, we were hungry…and now here you are, returned from Australia …a palikari!” she hugged and kissed me on my eyes, forehead and cheeks. She smelt of fine mint, “Come, let me see you,” she stepped back with her hands on her hips, her white hair in a neat bun on top of her head. She looked me up and down and broke into tears. We held each other. Demoklia was my aunt, Takis’ mother.

“Mother, he’s going to Turkey in a few days to visit Bafra,” he said half whispering.

She either did not hear him or decided to ignore it.

“You have so much to learn. Your mother didn’t tell you the whole story,” she said, taking my hand resting on the table. Her clasp was like a child’s, only a little more brittle, her hand warm and smooth.

“Did you know we prayed for you, my boy? Your family names were given to our priest and placed on the holy altar. We prayed for you and your family. Your father was a good man.” She bowed her head and crossed herself.

I looked forward to the time when I was not reminded of his death. She looked like an owl, with big glasses that made her eyes seem like saucers. Her white hair was parted in the middle, creating an oval frame straight down the centre. She was my mother’s older sister.

“Your mother was very young when she married. Yes, you were born when she was only 15. A baby is having a baby. We all loved you, and we played with you as a doll. But your mother doesn’t know all the stories, doesn’t know what happened in Turkey because she left to go to Australia. We heard the stories from your papou and yia yia, our father and mother.”

“I only knew my grandparents as a baby and can’t remember them. Now that my father has died, I wish to reclaim my Greek heritage.” I said.

“You have Greek parents, speak Greek, and are Orthodox—you have your heritage!” she smiled.

“I know, but I want to see where my grandparents came from. I want to breathe the air & stand on the ground they stood on.”

I don’t know how much your mother told you about your grandparents, so I’ll share what I know. She sat, hands clasped, leaning in, eyes locked on mine.

Your papou, a brave warrior. And your yiayia, equally courageous. They weren’t into that nationalist nonsense—neither Greek nor Turkish. Their fight was against injustice. When news reached the Greeks that the Turks were massacring our Armenian kin, the Greeks knew they’d be next. They armed themselves with guns, knives, any damn thing they could find. Those readying for battle fled to the hills and hid in caves. Sometimes, they’d venture to towns for supplies and clash with the Turks. But your papou and yiayia, stubborn as ever, stayed in the city despite the warnings of certain death.” She paused, raising her arms high, head held high. A sigh escaped her lips.

“One day, Greeks were herded into St. George’s little church. Men, women, children, the old, the young—all corralled inside, then the church was set ablaze. They all perished. Greek homes turned to ash. Your grandparents’ house, too, went up in flames. As it burned, everyone fled, chased by Turks on horseback. When Elis, your yiayia’s sister, tried climbing out of the window, a Turk on horseback spotted her and yelled, ‘Too beautiful to burn and die!’ He snatched her up onto his horse. We know ’cause Nicholas, a family friend, hid nearby, half his body burnt, watched it all unfold from the bushes.”

Somehow, your grandparents found their way to the hills and took shelter in caves. After a while, your papou and some men ventured back to town for supplies. They found nothing but ruin—no Greeks in sight. They combed the church, remnants smouldering, smoke twirling in the air. People lay there—charred, some decapitated—their clothes tarnished by smoke and soot. All dead. As they turned to leave, footsteps and gunfire echoed. Your papou gunned down a Turk while they hurried back to the hills. Little did they know that what happened in Bafra would be happening throughout our land.

Soon after, Greeks in the hills and everywhere else embarked on a journey to Constantinople and then fled to mainland Greece as refugees.

“Mother, tell him ’bout yiayia feeding the children during their trek to Greece,” Taki interjected.

“Your yiayia, a remarkable woman,” she said. “One day, after weeks of marching, exhaustion clawing at them, parched and famished, they reached the outskirts of Constantinople. Their group, about thirty strong, stumbled upon a trickling creek offering fresh water. They made camp by that creek that night. No food but water to quench their thirst and a campfire to warm their weary bones.

Yiayia shared the children’s hunger and felt it deep within her gut. With a commanding voice, she called out, “Come, children! I have food for you. Come!” Rising to her feet, she waved her hands, beckoning the children to gather. Soon, seven young ones huddled around her. Before her, a bowl of water sat as the children settled cross-legged or on their knees. Steady as a rock, yiayia held the bowl while her gaze fixed upon them. She spoke, her voice filled with faith, “The Mother of God hasn’t forgotten us.” In her tattered coat, she rummaged, retrieving a small icon of Theotokos—the Mother of God. “This icon shall nourish us,” she declared. The children leaned in, eager for a glimpse. They beheld Mary cradling her child, Jesus. “It’s a sacred icon, capable of miracles. I shall pass it on to you. Kiss it, make the sign of the cross, then pass it along.” Yiayia raised the icon to her lips, pressed a tender kiss, crossed herself, and handed it to the children. Each child, wide-eyed with anticipation, peered at the tiny icon, kissed it, made the sign of the cross, and passed it to the next in the circle. When the icon returned to yiayia, the children’s faces glowed with hope. Yiayia raised the icon above her head, then lowered it gently toward the water-filled bowl, uttering a prayer. Immersed in prayer, she lifted and immersed the icon three times.

When the prayer ended, Yiayia carefully dried the icon with a corner of her dress, stowing it back in her coat. “Now, children, this water is food. Come and eat.” She allowed each child to take a few mouthfuls, and soon, all the nourishment vanished. For that night, the children were fed, their hunger appeased.

I asked, my voice filled with curiosity, “Was it truly food?”

Dimoklea smiled and replied, “Well, the children ceased their cries and complaints of hunger. So, what do you reckon?”

Silent and awestruck, I pondered. After a while, I uttered, “I’m going to Bafra. I must.”

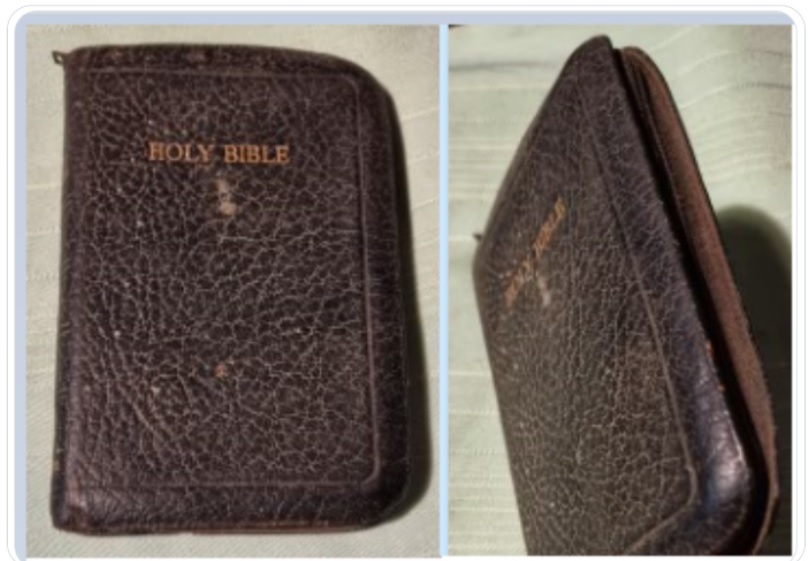

“All right, you’re set on going. I see your mind will stay the same. Stubborn and determined, just like your grandfather. I shall give you something that might aid you in finding people who knew your grandparents in Turkey.”

She rose from her seat and left the kitchen. Our gazes met. Taki shrugged and shook his head. None of us knew what she had in mind. After a brief absence, she returned, clutching folded paper and a photograph.

“Take this photo of your grandmother,” she said. “Your resemblance is striking. Anyone can see it. And take this letter.”

“A letter? What’s in it?” I inquired.

“It’s in Turkish, a letter from your grandaunt, your grandmother’s sister,” she replied.

“I thought everyone in our family was killed in Turkey. How could yiayia receive a letter from her sister?”

“Ah, remember her sister whom a Turk snatched on horseback? You know the tale now, just as well as your cousins do, but they’re unaware of this letter.” She waved the letter in the air.

“So, you’re saying a grandaunt remained in Turkey and might still be alive?”

“I doubt she’s alive now, for that would mean she’s over 120 years old! No, there might be a family who knows her. In this letter to your yiayia, she said she’s married and has children, and one of her children wrote it for her.”

“Hold on, hold on. It’s all happening too quickly. How did yiayia know where to send the letter?” I asked, shock evident in my voice.

“Yiayia simply addressed it to Bafra with Elis’ name on the envelope. People know each other in a village, and that’s how your grandmother’s letter reached her sister.” She paused, ensuring she had our undivided attention. “Now, I’ll translate the letter from Turkish.” Opening the already yellowed paper, she began reading it in Turkish, sentence by sentence, translating it into Greek.

The essence of the letter conveyed her immense joy upon receiving yiayia’s letter. She spoke of kissing her eyes and forehead, embracing her. She acknowledged that life continues, and although she’s now a different person and a mother, deep in her heart, she knows her true identity.

“Now, the most crucial element of this letter is the address from which it was sent—Kafkas Hotel, Bafra. Take this letter and the photo. The photo will reveal the physical resemblance to your grandmother. At the same time, the letter, written in Turkish, will indicate whom you seek and why.”

My cousin approached to examine the letter and photo in my hand. I declared, “Already, I have a solid starting point in finding someone who knew Papa and Yiayia. I might even discover relatives!”

Taki chuckled. “Well, you might find someone, but it might not be pleasant.”

I gazed at the photo and saw a similarity in the contours of our faces. As I observed the handwritten Turkish script in the letter, I perceived it as a gateway to my heritage and lineage.

Posted by stavr0s

Posted by stavr0s